The Language of Behavior

I find it necessary to increase awareness about the academic and emotional needs of children who have been impacted by trauma within the education community. I invited my wife to join me again on this blog post to add her voice and perspective to continue the conversation on incorporating trauma-informed care in the classroom. We were foster parents for five years, and during that time were able to adopt three of the children placed in our home. We closed our foster license after our third adoption, but the education, training, and ongoing research on the field of childhood trauma will forever be impactful to our lives and incorporated into our parenting and educational strategies.

I (Leslie) have found two practices that we learned in our behavioral management training have been the most helpful to me as a parent. Though these techniques were developed for kids impacted by trauma, they work wonderfully with all five of my children. The first strategy we use often is a “redo.” This is a second chance opportunity, where the outcome is a guaranteed win for the child. Last night, one of my children threw a fit, flailing around with his limbs, using unkind words, crying, and yelling to express what he wanted, which was a drink of water. I knew something had set him off - triggered him. He wasn’t in control of himself, but he did have a valid need for water. I took a deep breath to calm myself, gave him a tight hug to help soothe his nervous system, and spoke calmly and warmly. I told him, “I know that you need water, and my answer is yes, you can have water. Please ask me kindly and then we will get your water.” It took him a couple of minutes, during which I continued to stay with him, but he calmed down, and asked respectfully. I praised him and gave him his water bottle, and we went on about our day.

The other strategy we use often is a “time-in.” Many parents know the term “timeout,” but the difference between the two is based on proximity to and availability of the parent. In a “timeout,” the child is removed from the presence of others, which creates a disconnection in both physical distance and emotional support. In a “time in,” the child is removed from the activity or situation but not from the parent. The child has temporarily lost the privilege of independence but the connection to the parent remains. When I implement time-ins, I modify my actions to what my child needs in the moment. If they are obviously dysregulated, I will sit and hold them during the time-in until they are calm. If they need time to think about their actions, I sit them in a chair or on the floor or counter right next to me and continue what I was doing. With time-ins, the child remains directly next to me, and I am readily available to meet any physical or emotional need they may have as it arises. Once they voice (or display) they are ready, we discuss what happened and give them a chance to make it right, either through a redo or by apologizing (often times both).

As I (Joshua) was listening to the speakers during foster parent trainings on these and other behavior management techniques, I noticed several similarities to the classroom and I would wonder, “How can we address the student’s behavior in the classroom while keeping the relationships intact?”

As a teacher, we are trained in nonverbal communication, which helps us determine if a student is engaged in the lesson, confused by the material taught or lacking full depth of understanding. We use these skills to modify teaching strategies, assessments and curriculum everyday. What would happen if we applied the same skills to our assessment of and responses towards negative behavior as we do to learning? Often times, after a student misbehaves, the student is removed from the learning environment. Similar to a “time-out,” the student is disconnected from the teacher and the other students. At this time, a teacher or administrator speaks to the child about the negative behavior. When the student is allowed to return to the learning environment, the relationship with the teacher and other students is fractured and unrestored due to the removal process.

As I witnessed this cycle in my own school, I realized we needed to add some additional tools to our toolbox. During the school year, I assembled an amazing group of teachers, the “Relationship Action Team,” to implement and teach restorative practices, incorporating the principles of Trust-Based Relational Interventions (TBRI). One of the guiding principles of TBRI is following the IDEAL response. IDEAL is an acronym used to remind caregivers, including teachers, how to respond to challenging behaviors. As an educator, our response should be:

- Immediate - responding to the behavior as quickly as possible

- Direct - face-to-face, with eye contact, in close proximity to the child, not across the room

- Efficient - using the least amount effort necessary, meaning maintain a low volume of our voice, the least sternness in tone, and the fewest number of words to correct the behavior

- Action-based - allow the child to practice appropriate behavior and praise them once that is accomplished

- Level - our response is aimed or leveled at the behavior, not at the child.

As a group, we had to determine what our goal was for student behavior and how we were going to create safe, healthy and authentic interactions with our students. If a student doesn’t believe you care about them, then the response to redirection or correction will become defensive. To begin the process, we needed to adjust how we conducted our own classroom practices and how we interacted with students. When a student wasn’t conducting themselves appropriately or displayed anger, teachers began using a form of a “time-in” and using the IDEAL response to de-escalate the situation. Once the student was given an opportunity to calm down, teachers provided opportunities for students to conduct “redos”.

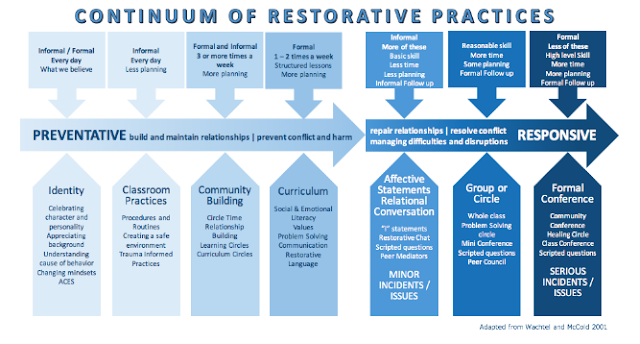

In addition to using the IDEAL responses, we decided to implemented social-emotional practices in their classroom to establish healthy student relationships, provide opportunities for safe communication and teach appropriate student behavior. To assist in this goal, the Relationship Action Team learned about a proactive and reactive system called Restorative practices. The philosophy and core belief of restorative practices is to build healthy relationships with all students.

By creating healthy relationships and positive interactions, we are able to reduce harmful behavior by providing clear expectations, modeling appropriate communication, and creating safe environments. If students were in conflict, restorative practices provided a system to repair harm, restore relationships, resolve conflict, and establish responsibility and ownership. The four practices implemented were relationship circles, restorative circles, relationship agreements and reflection activities.

Relationship Circles

As a proactive measure In the classroom, teachers utilize “relationship circles” to allow every student an opportunity to share in a safe space. To construct a relationship circle, each student positions themselves in a circle, the teacher is the moderator and the only person who is allowed to speak is the person holding the “talking object,” which usually is a classroom item. The structured practice of one person talking and everyone else listening allows the students to feel a sense of empowerment, inclusiveness, and belonging within a controlled setting. The questions vary but usually the questions were targeted for the students to share about non-threatening or high emotional subjects. For instance, “What is your favorite soda?” or “What sport do you enjoy playing?” This process allows the students to share about themselves, which creates connections with other classmates and a stronger bond as a group.

Restorative Circles

By using the relationship circles, the students are taught the basic structure of the “circle.” In a restorative circle, the function and structure is the same as the relationship circle. The teacher is the facilitator and the one holding the “talking object” is the person who is allowed to speak. The difference is the restorative circle is in response to a fractured relationship, and is intended to resolve the conflict and restore the relationship. In the restorative circle, it is important to establish three rules:

- Only speak if you have the “talking object” to establish safety.

- Be honest and stick to the facts.

- Speak without using attacking language towards the other people involved in the circle.

As a facilitator, it is important to remind the students of these rules as it is extremely natural for students to speak about the actions of others before looking at their own actions. This structured process provides students with a healthy model for reflection, problem solving, and conflict resolution.

Relationship Agreements

The relationship agreements are a collaborative activity with the class or select group of students to create shared expectations between all parties (student to student, teacher to student, and student to teacher). The agreement is created to provide the students an opportunity to have input and ownership in the expectations. The relationship agreement is a working document, which has the opportunity to be changed and modified throughout the year. The teachers had posters on the wall or laminated agreement sheets posted on the student desks as daily reminders for the students and the teacher. Many days, the students would respectfully police themselves by pointing out that another student’s behavior or interaction wasn’t meeting the relationship agreement.

Reflection Activities

The reflection activity is a series of questions for the student to answer, verbally or in writing, after a student participates in an unhealthy behavior. The activity is meant to allow the student to see the effects of their choices, how their actions impacted others and how the other parties involved felt after the interaction. Often, when a student acts inappropriately, we ask “what were you thinking?” or “Why would you do that?” Instead, we need to be intentional about asking reflective questions to allow students an opportunity to take ownership of their actions, see the effects of the behavior, and develop a plan to rectify the damaged relationships.

Similar to a doctor, educators have to diagnose student’s problematic behavior by looking at the symptoms. Negative behavior is a symptom to a larger problem, which is deeply rooted in their social and emotional health (see image above). When students have large emotions, which result in big behaviors, we must model composure not mirror chaos. Each student is different and has very different experiences in their life. We can not assume that each child understands or knows how to interact appropriately with adults or authority. Our tactics with student behavior must be differentiated, the same as we do with academics. If we view behavior as a form of communication instead of a personal quality, the misbehavior has a purposeful function to determine the unmet need. Behavior is a form of communication and we cannot enhance learning without improving the emotional wellbeing of the heart.

In this blog series, Leslie and Joshua Stamper have taken a deeper look at essential aspects of trauma informed practices, Trust Based Relationship Interventions, and Restorative Practices from the perspective of a parent and a school administrator. You can find our other posts on trauma here: In the Face of Trauma and History of Trauma.